History of Tobacco Impacting African-American Communities

For decades, the tobacco industry has regularly used popular African-American culture as a way to boost sales. They poured millions of dollars into targeted marketing campaigns to get minorities, especially African-American youth, to begin a potentially deadly addiction to smoking.1,2

Sadly, this continues even today. Tobacco companies are targeting African-American communities, using special tricks and tactics hoping to recruit more “replacement smokers” from these groups.3

How big is this issue? Tobacco-related diseases kill more African Americans each year than AIDS, car crashes, murder, drugs or alcohol abuse… combined. 4

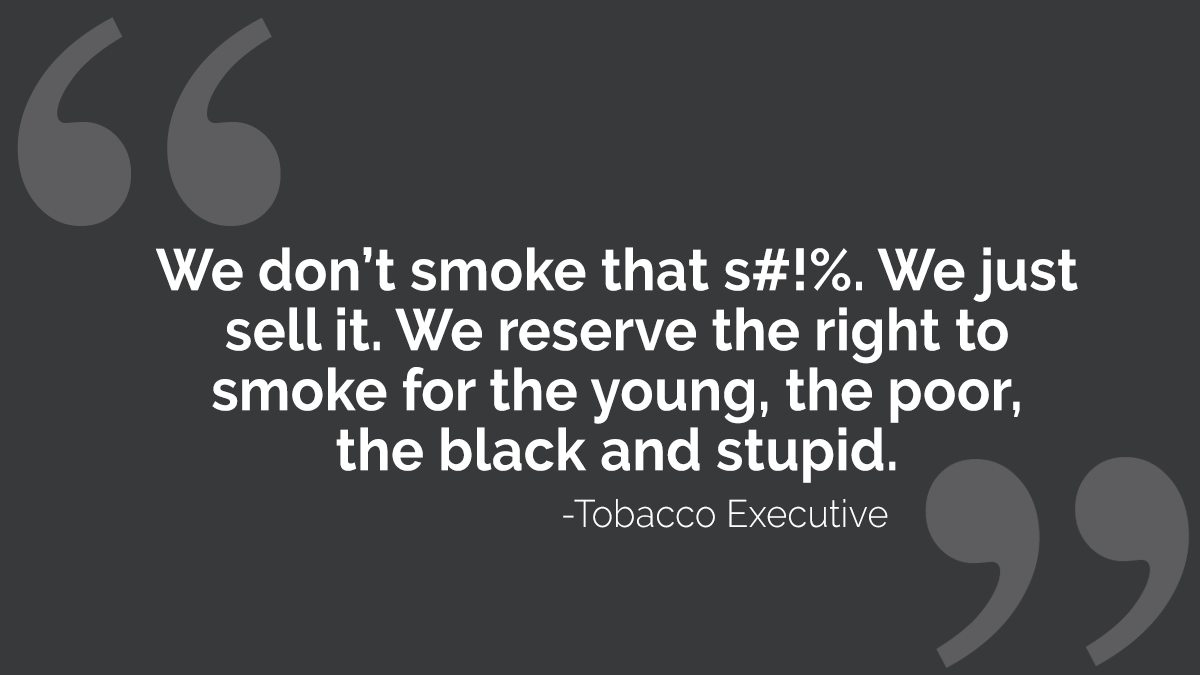

When considering why they went down this road, it’s tempting to think of what one tobacco industry official reportedly said when asked why he personally didn’t smoke.

What have the tobacco companies done for decades? They’ve wrapped their products in African-American culture to increase affinity and ultimately acceptance of cigarettes and other types of tobacco.

How Did We Get Here?

For more than 50 years, tobacco companies created advertising, events and even special cigarettes they believed would be the best to get African Americans smoking. 5,6 Here are a few examples.

The 1950s

In 1955, Liggett & Myers decided to design and launch a campaign aimed to get more African Americans hooked on Chesterfield brand cigarettes. Chesterfield began advertising heavily in magazines like Ebony and Our World, and even designed advertising to appear in storefronts and retail locations featuring African-American sports figures endorsing and promoting the company’s cigarette brand.7

Further looking to penetrate into the community, Liggett & Myers underwrote a series of documentary films associated with Chesterfields and referencing African-American achievements. The company then showed these films at over 100 African-American colleges across the country, and distributed free cigarettes at every screening.8

The tactic worked. They reached nearly a million people on campuses this way, mostly African Americans. Another 3 million people saw them when the Chesterfield-branded documentaries aired in 500 theaters. Each of these theaters were in predominantly African-American neighborhoods.9

The 1960s

In the 1960s, the tobacco industry ramped up its efforts, and the targeted marketing took the form of buying up advertising in popular magazines in the African-American community.

Consider what happened with Ebony over this time: In 1950, Ebony had half the number of cigarette ads found in Life magazine (Ebony: 16 vs. Life: 31). By 1962 this number had completely switched, with Ebony having double the number of cigarette ads found in Life (Ebony: 57 vs Life: 28).10

It was also during this period that tobacco companies started actively promoting menthol cigarettes, carefully selecting models to most appeal to the growing African-American populations in major American cities.11

Tobacco companies also made sure to funnel huge donations to African-American causes and activist organizations, funneling millions of dollars into these groups in the hopes of influencing legislation and driving up sales in the African-American community. An in-depth analysis from the Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education explained: “The industry established relationships with virtually every African American leader and organisation [sic] for three specific business reasons: to increase African American tobacco use, to use African Americans as a frontline force to defend industry policy positions, and to defuse tobacco control efforts.”12

The 1970s

As time went on, various cigarette brands jumped on ways to introduce African Americans, especially younger African Americans, to their products.

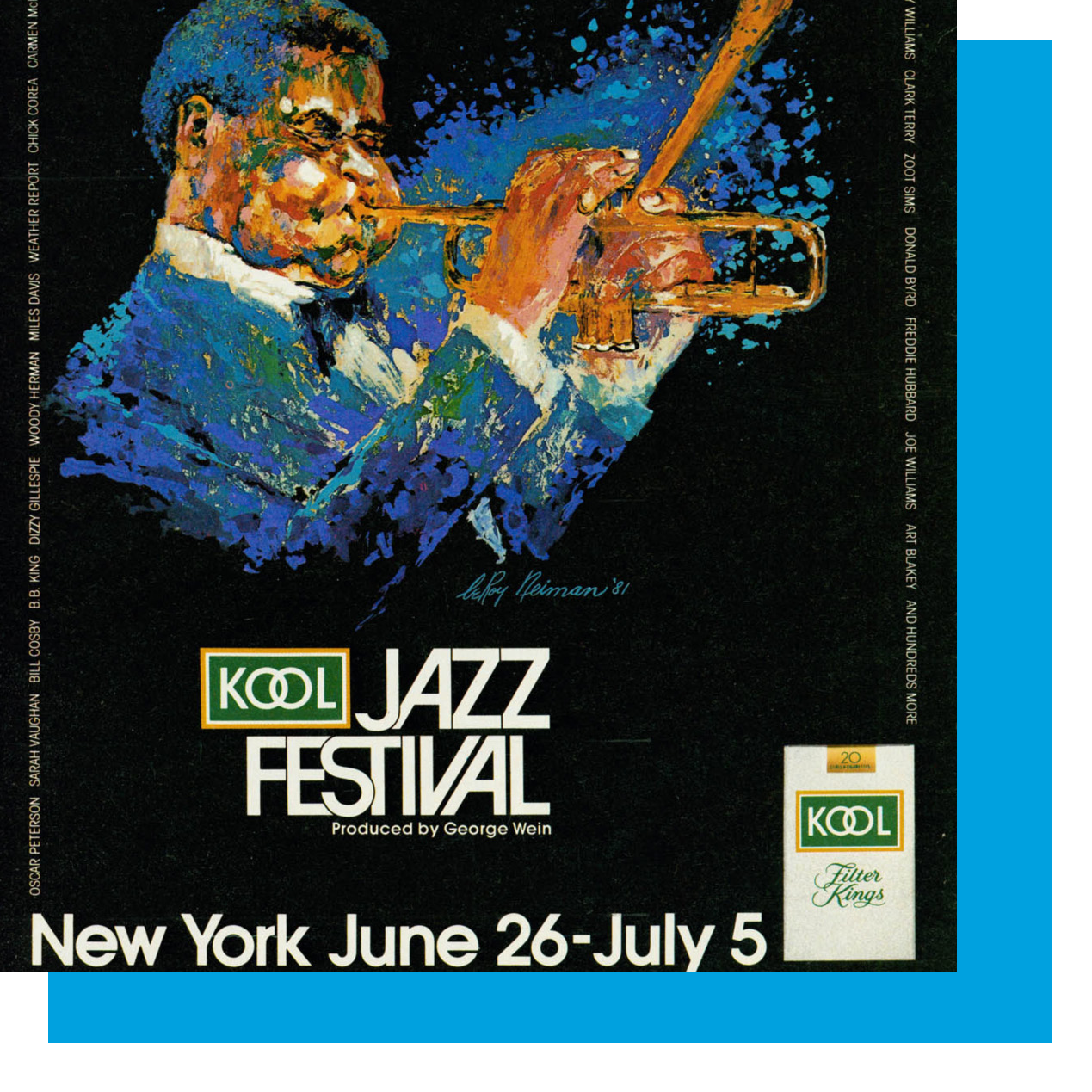

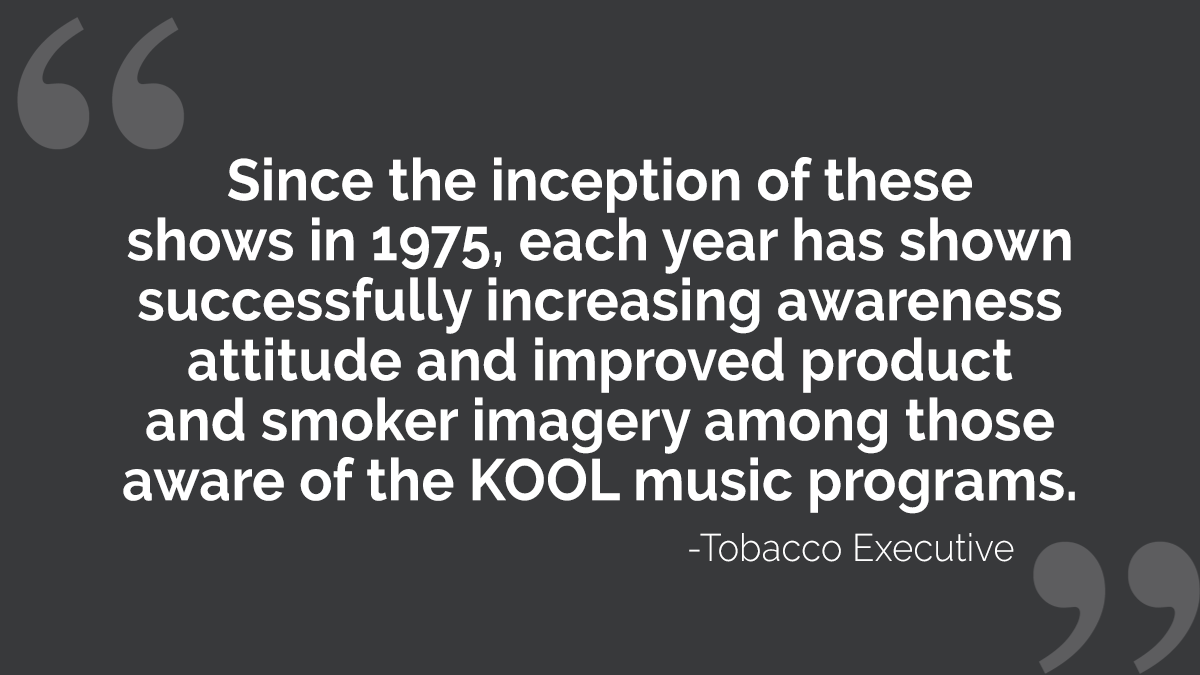

Kool sponsored major events like the KOOL Jazz Festival.13 This attempted to make the brand popular by associating it with popular music acts of the day.

The cigarette-related marketing was almost exclusively geared towards African-American potential customers. By 1980, KOOL was applauding itself in internal documents for having established “the premier events in Black soul music” with an attending audience it cited as “90% Black.”14 Early shows hired acts like Marvin Gaye, Smokey Robinson and The Staple Singers.15

Why did they do these concerts? Again, the answer can be found in the actual words from tobacco industry executives at the time.

Running on Fumes

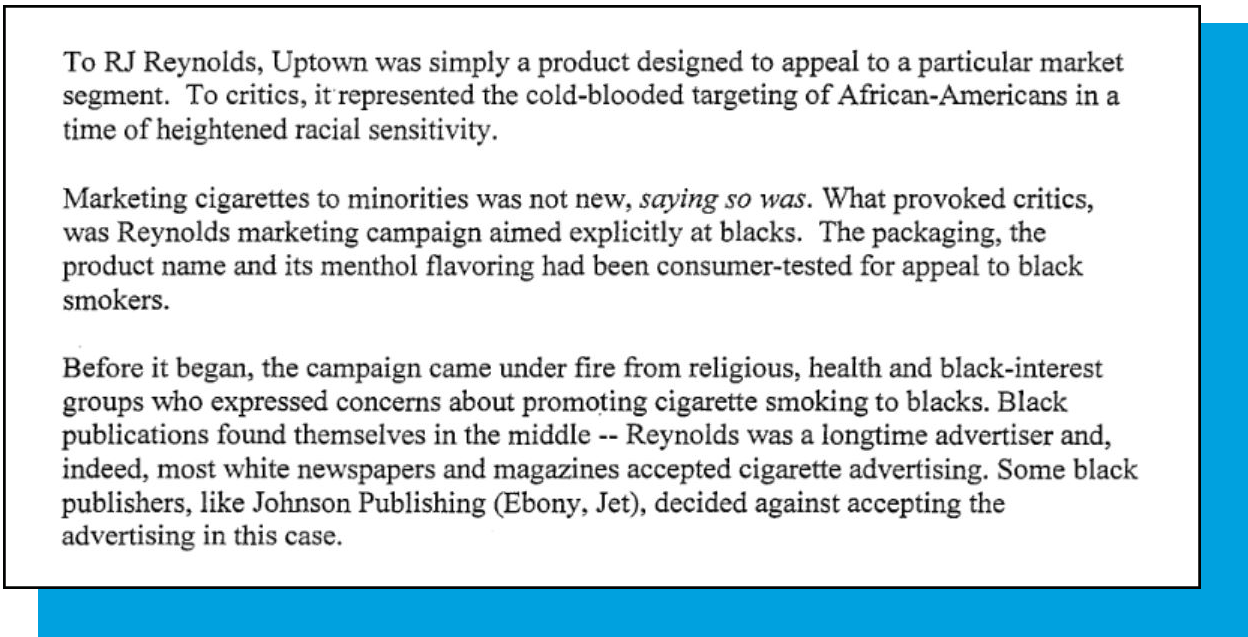

In late 1989, R.J. Reynolds tried and failed to launch a new brand, aimed squarely at African-American smokers, called Uptown. The marketing program for this brand launch included heavy advertising in “targeted black print media (Jet, Essence, Ebony, key newspapers)” as well as a “continuous key black night club presence.”16

The plan included selling Uptowns in 10-packs rather than packs of 20, which “addresses price sensitivity”… a delicate way of saying the product needs to be cheap enough for even those with low income to continue to buy.17

Community leaders finally stepped in, declaring enough was enough.18 Consider these lessons learned as shared in an R.J. Reynolds internal memo, “Anatomy of a Failure – Uptown Cigarettes.”

KOOL tried to sneak back in the game of tying African-American performers with its products, popping up occasionally at things like The House of Menthol series mirroring the House of Blues in 1998 and the KOOL MIXX promotion in 2004, celebrating hip hop.19

Again, regulators stepped in. The makers of KOOL had to settle a lawsuit that pointed out the campaign was a clear violation of the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement because of its targeting of African-American youth.20,21,22

These are just a few of the stories over the years of tobacco companies specifically setting up campaigns to get African Americans hooked on their deadly products.

Making the Product Even Deadlier

Often, the marketing of tobacco products encouraged African Americans to consider menthol cigarettes, which have additional health risks of their own. Nearly 9 of every 10 African-American smokers (88.5%) aged 12 years and older prefer menthol cigarettes.23 Menthol is one of the reasons the African-American population continues to be especially hard hit by the deadly health effects of smoking.

Some of the risks of menthol:

- Menthol makes cigarette smoking easier to start and harder to quit.24

- The flavoring allows the lungs to expand further, and allows more of the toxic and cancer-causing chemicals in cigarette smoke to be absorbed into the body, which can lead to addiction, disease and death.25,26

- Compared to adults who smoke non-menthol cigarettes, adults who smoke menthol cigarettes make more attempts to quit smoking and have a harder time quitting.27

Again, tobacco companies know through extensive market research that African-American consumers overwhelmingly prefer menthol cigarettes. These companies continue to use price promotions such as discounts and multi-pack coupons, popular in these communities, as ways to continue to increase sales.28

Okay, so that’s a lot of history. But have times changed?

It’s important to know the history of how tobacco companies repeatedly targeted African-American consumers. It’s also an unfortunate fact that this disparity continues. Tobacco companies promote and market their products much more heavily in African-American communities even today.

There are many ways tobacco companies currently target African Americans.

- In addition to tobacco companies placing advertising in a larger amount of African-American publications, these communities have been more exposed to cigarette ads than white communities.29

- A recent study found that stores in predominantly African-American ZIP codes are more likely to engage in tactics like placing tobacco products near candy, placing tobacco ads in the line of sight of children and offering price promotions like small cigars selling for under $1.30

- Around the country, areas with a higher African-American population also have a much higher number of tobacco retailers.31

- Point-of-sale advertising — those bright promotional posters you see around the register at convenience stores and other retailers — is also dramatically different in African-American communities, in addition to being much more frequent.32

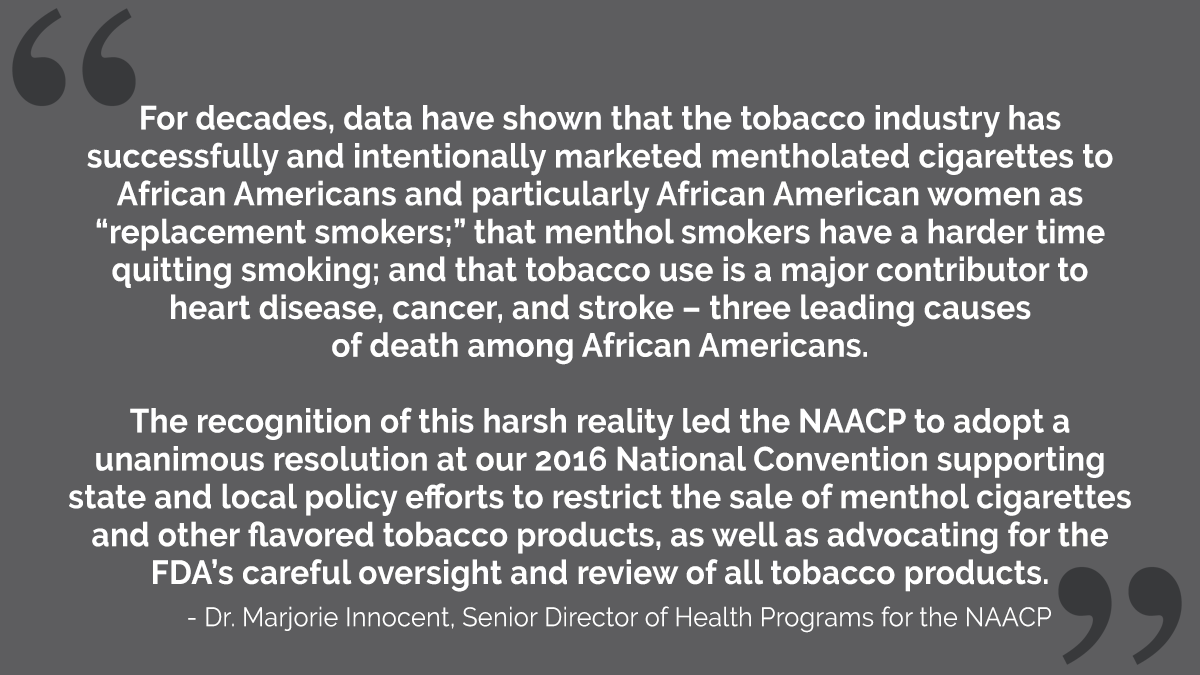

Dr. Marjorie Innocent, Senior Director of Health Programs for the NAACP, summed it up brilliantly:

What has the impact of all this been on the community?

- Tobacco use is an epidemic in the African-American community, and the leading preventable cause of death.33

- Tobacco-related diseases kill more African Americans each year than AIDS, car crashes, murder, drugs or alcohol abuse… combined.34

- Tobacco use is a top contributor to the three leading causes of death among African Americans: heart disease, cancer and stroke.35,36,37

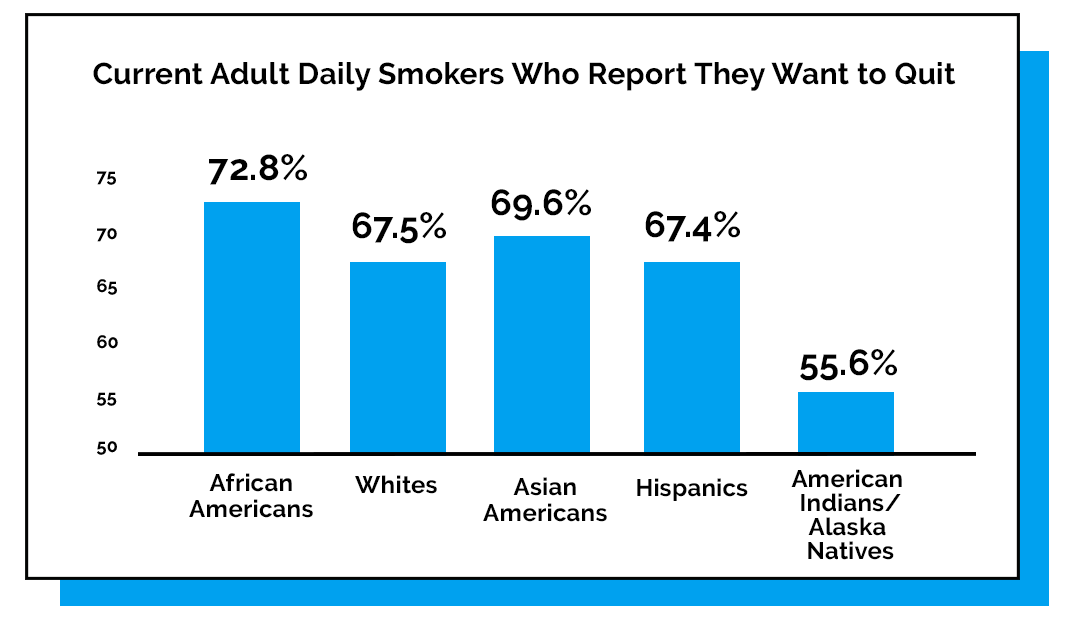

- Diabetes is the fourth-leading cause of death in this group.38 The risk of developing diabetes increases 30 to 40% for cigarette smokers compared to nonsmokers.38Despite the fact that African-Americans smoke fewer cigarettes than whites on average and start smoking at an older age, they are more likely to die of tobacco-related diseases.40,41,42,43,44 But there’s good news, right? There are many reasons to be optimistic. Together, we have the opportunity to make progress in changing the future to one with better health and longer lives across African-American communities in Florida.

Major nationwide organizations such as the NAACP and NAATPN work to educate about the health effects of smoking and the history of Big Tobacco targeting these communities. They encourage action and provide information on important prevention initiatives.Is there anything I can do to make a difference?There are many things you can do in your community and among your family and friends to fight back.

- Share this post and other posts like it with anyone you think would be interested in learning the tricks and tactics tobacco companies have used to infiltrate African-American communities across the country.

- Look to limit tobacco-related ads in your communities. Identify areas where it’s being promoted near schools or other areas where young people might be introduced to tobacco and enticed to smoke. Help educate local leaders about this topic. To learn more about getting involved, visit tobaccofreeflorida.com/get-involved/

- Work with local employers to encourage workplace policies that help people quit and reduce secondhand smoke exposure.

- Tobacco Free Florida has tools and services that are proven to help you quit smoking, and available completely free regardless of insurance. Additional information is available today at tobaccofreeflorida.com/quityourway or by calling 1-877-U-CAN-NOW.

We can continue the momentum that is already underway. Millions of lives across Florida are at stake. We can do it. You can help. To learn more about tobacco companies marketing to African Americans, read Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids’s fact sheet.

1 Hafez N, Ling PM. Finding the Kool Mixx: how Brown & Williamson used music marketing to sell cigarettes. Tob Control. 2006;15(5):359–366. doi:10.1136/tc.2005.014258

2 Phillip S. Gardiner, The African Americanization of menthol cigarette use in the United States, Nicotine & Tobacco Research, Volume 6, Issue Suppl_1, February 2004, Pages S55–S65, https://doi.org/10.1080/14622200310001649478

3 Center for Public Health Systems Science. Point-of-Sale Strategies: A Tobacco Control Guide. St. Louis: Center for Public Health Systems Science, George Warren Brown School of Social Work at Washington University in St. Louis and the Tobacco Control Legal Consortium, 2014 [accessed 2019 September 27].

4 American Psychological Association: Health Disparities Initiatives programs and initiatives: Tobacco Health Disparities. December 2014. [accessed 2019 September 27.]

5 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Tobacco Use Among U.S. Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups—African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office on Smoking and Health, 1998 [accessed 2019 September 27].

6 Hafez N, Ling PM. Finding the Kool Mixx: how Brown & Williamson used music marketing to sell cigarettes. Tob Control. 2006;15(5):359–366. doi:10.1136/tc.2005.014258

7 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Tobacco Use Among U.S. Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups—African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office on Smoking and Health, 1998. [accessed 2019 September 27].

8 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Tobacco Use Among U.S. Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups—African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office on Smoking and Health, 1998. [accessed 2019 September 27].

9 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Tobacco Use Among U.S. Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups—African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office on Smoking and Health, 1998. [accessed 2019 September 27].

10 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Tobacco Use Among U.S. Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups—African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office on Smoking and Health, 1998. [accessed 2019 September 27].

11 Phillip S. Gardiner, The African Americanization of menthol cigarette use in the United States, Nicotine & Tobacco Research, Volume 6, Issue Suppl_1, February 2004, Pages S55–S65.

12 Yerger VB, Malone RE. African American leadership groups: smoking with the enemy. Tobacco Control 2002;11:336-345. https://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/11/4/336

13 Hafez, Navid, and Pamela M Ling. “Finding the Kool Mixx: how Brown & Williamson used music marketing to sell cigarettes.” Tobacco control vol. 15,5 (2006): 359-66. doi:10.1136/tc.2005.014258

14 “Kool Music Program – Background Information.” https://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ofn14f00.

15 Unknown. KOOL MUSIC PROGRAM – BACKGROUND INFORMATION. 1980 January. Brown & Williamson Records. Unknown. https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/docs/xryx0134

16 Government relations/PR plan: Project UT. Marketing fact sheet. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Co. 1989. Bates No. 507727693/7695. Available at: https://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ixv14d00. [accessed 2019 September 27].

17 Government relations/PR plan: Project UT. Marketing fact sheet. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Co. 1989. Bates No. 507727693/7695. Available at: https://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ixv14d00. [accessed 2019 September 27].

18 Government relations/PR plan: Project UT. Marketing fact sheet. RJ Reynolds Tobacco Co. 1989. Bates No. 507727693/7695. Available at: https://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ixv14d00.[accessed 2019 September 27].

19 RJR. THE NEW JAZZ PHILOSOPHY TOUR 2006 (20060000) MUSIC KNOWS NO LIMITS. 2006. RJ Reynolds Records. Unknown. https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/docs/llnf0019

20 Company News; Reynolds Settles Suits in 3 States Over Cigarette Ads. The New York Times. 7 Oct. 2004. https://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9E0DE1D9173BF934A3575

21 “Black musicians”. https://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_main/images_body.php?token1=fm_img16986.php. [accessed 2019 September 27].

22 Office of the New York Attorney General. Landmark Settlement of “kool Mixx” Tobacco Lawsuits. https://ag.ny.gov/press-release/landmark-settlement-kool-mixx-tobacco-lawsuits. [accessed 2019 September 27].

23 Giovino GA, Villanti AC, Mowery PD et al. Differential Trends in Cigarette Smoking in the USA: Is Menthol Slowing Progress? Tobacco Control, doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051159, August 30, 2013

24 U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Preliminary Scientific Evaluation of the Possible Public Health Effects of Menthol Versus Nonmenthol Cigarettes, July 2013.

25 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Tobacco Use Among U.S. Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups—African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office on Smoking and Health, 1998 [accessed 2019 September 27].

26 Ton HT, Smart AE, Aguilar BL, et al. Menthol enhances the desensitization of human alpha3beta4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Mol Pharmacol 2015;88(2):256-64 [cited 2017 Oct 27].

27 Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee. Menthol Cigarettes and Public Health: Review of the Scientific Evidence and Recommendations. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration; 2011.

28 Center for Public Health Systems Science. Point-of-Sale Strategies: A Tobacco Control Guide. St. Louis: Center for Public Health Systems Science, George Warren Brown School of Social Work at Washington University in St. Louis and the Tobacco Control Legal Consortium, 2014 [accessed 2019 September 27].

29 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Tobacco Use Among U.S. Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups—African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office on Smoking and Health, 1998 [accessed 2019 September 27].

30 Laestadius, Linnea & Sebero, Heather & Myers, Allison & Mendez, Edgar & Auer, Paul. (2018). Identifying Disparities and Policy Needs with the STARS Surveillance Tool. Tobacco Regulatory Science. 4. 12-21. 10.18001/TRS.4.4.2.

31 Rodriguez, D, et al., “Predictors of tobacco outlet density nationwide: a geographic analysis,” Tobacco Control,published online first on April 4, 2012.See also Lee, JGL, et al., “Inequalities in tobacco outlet density by race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status, 2012, USA: results from the ASPIRE Study,” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, published online March 1, 2017

32 US Department of Health and Human Services. Tobacco Use Among US Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups—African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Dept of Health and Human Services, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 1998.

33 Ho, J. Y., & Elo, I. T. (2013). The contribution of smoking to black-white differences in U.S. mortality. Demography, 50(2), 545–568. doi:10.1007/s13524-012-0159-z

34 American Psychological Association: Health Disparities Initiatives programs and initiatives: Tobacco Health Disparities. December 2014. [accessed 2019 September 27].

35 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Tobacco Use Among U.S. Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups—African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office on Smoking and Health, 1998 [accessed 2019 September 27].

36 Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: Final Data for 2014. National Vital Statistics Reports, 2016;vol 65: no 4. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics [accessed 2019 September 27].

37 Heron, M. Deaths: Leading Causes for 2010. National Vital Statistics Reports, 2013;62(6) [accessed 2019 September 27].

38 Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: Final Data for 2014. National Vital Statistics Reports, 2016;vol 65: no 4. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics [accessed 2019 September 27].

39 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014 [accessed 2019 September 27].

40 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Tobacco Use Among U.S. Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups—African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office on Smoking and Health, 1998 [accessed 2019 September 27].

41 Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: Final Data for 2014. National Vital Statistics Reports, 2016;vol 65: no 4. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics [accessed 2019 September 27].

42 Heron, M. Deaths: Leading Causes for 2010. National Vital Statistics Reports, 2013;62(6) [accessed 2019 September 27.

43 Schoenborn CA, Adams PF, Peregoy JA. Health Behaviors of Adults: United States, 2008–2010. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 10(257) [accessed 2019 September 27].

44 American Lung Association. Too Many Cases, Too Many Deaths: Lung Cancer in African Americans. Washington, D.C.: American Lung Association, 2010 [accessed 2019 September 27].